This is part 3 of the series of blog posts that is elaborating on some of the methods in the list of managers’ panaceas [1], a list of anticipated antisystemic (sub-optimising) methods that Dr. Russell Ackoff brought up in the middle of the 1990s. Continuous Improvement on organisations will be the subject today, and is many times used as a collection for any kind of improvement. The PDCA cycle is a method that is commonly connected to Continuous Improvement, and both PDCA cycles and Continuous Improvement have strong connections to Toyota.

First a reminder that on the whole only continually improvements can be done even in production. This is due to the synchronisation needed between the parts when the respective part’s improvements are executed at the same time, for example takt time change. The parts can (and must) themselves be continuously improved, as long as they do not affect another part. This goes for any context, production, service, product development, etc., but is much easier as in a clear context like production.

Dr. Russell Ackoff was convinced, even though improvements generally are good things to do, that Continuous Improvement in most cases was sub-optimising, when done incorrectly; on the parts of an organisation. We will elaborate on organisational Continuous Improvement to understand if it is always sub-optimising, or when, and in that case how it can be performed in order to not sub-optimise.

The word continuous in Continuous Improvement gives the impression that it is good to do improvements as fast as possible on any part in a system. Unfortunately, it does neither state if it is possible to do Continuous Improvement in product development on interdependent parts (complex system) nor state anything about synchronisation for improvements done on the other parts either in production (clear system) with independent parts. This have led to tremendous misconceptions about the meaning of Continuous Improvement and when and how it can be performed. This can be seen especially in Agile product development using the Continuous Improvement from Toyota/Lean production without consideration about the change of context. This together with a focus on queues in Agile, due to the misunderstanding of WIP inventories in Toyota/Lean Production, has many times led to a culture of non-planning. Planning is context free and is something our specie has known since ancient times, a necessity to avoid a mess. Since queues are only a symptom, neither WIP Limits, nor Process Cycle Efficiency calculations nor other measurements, nor any other method, can solve the problem with queues directly. Only taking care of the root causes to queues can and no Continuous Improvement in the world can make it better either.

Product development has strong interrelationships between the parts. This means that all measurements done on parts of a system that has strong interrelationships, are antisystemic, which in turn means that we will sub-optimise our own organisation if we are trying to do changes that are built on the results of the measuring of the parts. So, measurements must only be done on the whole company*, or carefully be used on bigger working parts, like projects, that are making a full delivery of something; a product or service.

Measuring on an Agile team is a clear example of a sub-optimising Continuous Improvement, due to measuring on a too low level, if it only is a part that together with several other teams deliver something bigger. Only the bigger delivery can carefully be measured, because measures on Agile teams will give sub-optimisations with unintended consequences that can never be foreseen, avoided or most of all, not understood. It is not better than a silo improving itself and probably Continuous Improvement in teams is worse, since there are so many teams with retrospectives every second week. With only metrics on team level, no team know what changes other teams will do in order to improve themselves. Every change by a team gives unintended consequences somewhere else, since it is a sub-optimising change. A Walk in the dark for all teams respectively in the Fitness landscape.

If we look into Toyota’s Kaizen, it uses the PDCA cycle [1], or the PDSA cycle** (S – Study) that Dr. Edwards Deming promoted. Even though production is linear, the Toyota Production System with its takt time, consists of tightly connected processes, see this blog post about Overlapping Concurrent Sequences. This only makes it possible to do synchronised improvements and therefore continually, making Continual Improvement*** the more appropriate notion. So, the change from continuous to continual is definitely not hair-splitting; this is about understanding our organisations as the complex adaptive systems they are and also that the Toyota Production System also requires continual updates. The notion was also changed already in ISO 9001:2000 [4], but for another reason, and stated with this motivation; “continuous was unenforceable because it meant an organization had to improve minute by minute, whereas, continual improvement meant step-wise improvement or improvement in segments”.

This means that many changes done at a Toyota plant need to be fully synchronized within the whole plant, especially when changing the takt time or merging or splitting processes. Of course, carefully planned changes within the processes themselves are also done on a continual basis, without synchronisation with the other processes, to test new improved way of working. Another very important aspect to reflect on, is the frequent fluctuations of demand (which will change the takt time), making it necessary to have many persons within a process. This, so that it is easy to change the number of team members within the process, by changing the different steps within the process, when the takt time is changed. But, the tight connection between the processes, also means that even if an improvement within a process does not have effect in the current takt time, it may well have when the takt time changes. For a more thorough explanation on the Toyota way of working regarding their waste reduction, see here****.

If we change our view from production and its repetitions, to complex organisations doing non-repetitive work with many collaborating teams working for a common goal, it is even more obvious with the above reasoning. We need to call it Continual Improvement, and the improvements must be synchronised, but we must still be very careful that we are not sub-optimizing on the whole.

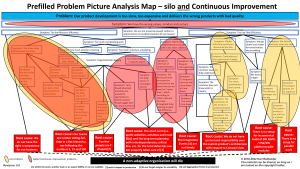

But remember that today we have a great advantage; we have our set of principles, that we have derived our Prefilled Problem Picture Analysis Map from. This means that when we have organisational problems, the first step is always to ask multiple why and map them to our root causes and solve the root causes. And, since we are sure that we are not sub-optimising our organisation when we are solving root causes, this is our first choice when we are solving our problems the Systemic Organizational Systems Design – SOSD method*****. Because, without securing that our organisation is following our set of principles, we can never ever achieve real System Collaboration and make our organisation flourish.

Since the concept of Continuous Improvement is derived from Toyota production System, they are already taking it to its perfection, and by acting systemically even in their product development, they are not risking any sub-optimisation.

Conclusion

Continuous Improvement is sub-optimising (antisystemic) when done on parts that to not fit together to a united, unified and well-functioning whole, but the great news is that Our Prefilled Root Cause Analysis Map – for organisations, ver. 0_99 makes it possible to make future Continuous Improvements fully systemically. And for Agile teams it means that we can change their Walk in the dark in the Fitness landscape, to a Walk in the park by fixing the root causes and that without even a glance at the Fitness landscape.

Regarding Continuous Improvement in our Prefilled Problem Picture Analysis Map, it is already obvious that Continuous Improvement is trying to optimise on the parts or layers, and that Continual Improvement will make it somewhat better, when there is synchronisation. But still our root causes need to be solved to act fully systemically, which leads to no risk for unintended consequences, meaning that we are avoiding sub-optimising effects. Here are some examples of Continuous Improvement efforts that are sub-optimising in our map; 1a) niching efforts per silo, department, section, group, team, etc, in order to solve the left pain point, which is totally contrary the needed solution, 1b) or trying to improve processes by themselves in a silo by itself, 2a) Agile teams trying to improve by themselves by retrospectives or 2b) wrongly focus on the queues, the two middle sub-optimising areas, also discussed in this blog post, 3) trying to make the culture better, see this blog post for more information, the upper sub-optimising area.

Fairly easy judgement.

Dr. Ackoff Panaceas

2 – 0

In the next blog post we are going to dissect the next method in the list of managers’ panaceas; Benchmarking.

C u then.

*More about measurements:

Note that we need to make a big distinction between the Line organisation and the working parts, the projects. Measurements done on a silo in the Line organisation, will strongly affect the projects, the working parts. We have seen this in earlier blog posts, where specialisation is absolutely the biggest problem for a traditional Line organisation with silos and working projects. So, measurements on the Line organisation must only be done on company level. This is called measure-up by Mary Poppendieck, i.e., a manager is measured on the level above to achieve transdisciplinary work between all managers at the same level.

**due to the C – Check become too much of inspection, instead of deep analyse, and also viewed as tampering with the meaning of Shewhart’s original work [2], according to Deming [3].

***a broader term preferred by W. Edwards Deming to refer to general processes of improvement and encompassing “discontinuous” improvements– that is, many different approaches, covering different areas.

****Toyota realised many years ago, when they more or less reached the end of the road for removing waste in their production with their current thinking, that they increased the risk for sub-optimisation. My belief is that they by their Continual Improvements fulfilled our planning principle close to perfection, by using the Overlapping Concurrent Sequences and their ambition towards the optimal takt time. This is the reason why they do not talk about Ohno’s 7 waste from 1978 anymore (the first edition of The Toyota Production System came out 1978 in Japanese and 1988 in English), and instead since many years instead talk about 4 waste [5], where one of them is the dominant waste maker, the Excessive Workforce, which generates all other sorts of waste. Toyota started to focus more and more on multi-I-shape, which they also made as the career ladder for their employees, besides a career as a manager. This meant that the workers learnt more and more other processes and split lines, and in that way, Toyota also solved our T-shape/multi-I-shape principle, meaning an increased systemic thinking.

Note that Toyota’s change in waste thinking means, that if we continue to use the 7 wastes, which is three decades old information from Toyota and transfer it to product development as well, we are not only using out-dated antisystemic-making information and not understanding the why, we have really not understood what Lean means; a never-ending journey.

*****The only systemic way is to solve the root causes to a symptom. That means dissolving the symptom, i.e., that we make a redesign and create a new system where the symptom no longer appears; we are dissolving the symptom. That is coherent with system and complexity theory, which states that a problem cannot be isolated and cured, in the same way that the parts themselves are not independent, since they are always interacting with the other parts of the system. But, when you dissolve a problem, you change the system to a new system, so there are no contradictions.

[1] Wikipedia. The PDCA cycle. Link copied 2018-12-15.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PDCA

[2] Moen, Ronald. Foundation and History of the PDSA Cycle.

Link copied 2018-12-15.

https://deming.org/uploads/paper/PDSA_History_Ron_Moen.pdf

[3] Wikipedia. Deming, William Edwards. Biography. Link copied 2018-12-15.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Edwards_Deming

[4] Continual Improvement Auditing. Link copied 2018-12-15.

http://www.qualitywbt.org/FlexTraining/ASP/content/sections/A12/pdfs/01al-vs-ous.pdf

[5] Monden, Yasuhiro. 2012. Toyota Production System: an integrated approach to just-in-time Fourth Edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.