This is the last and concluding blog post in this series about Toyota thinking, values and principles [1] [2], which unfortunately has been misinterpreted in many methods and frameworks, making a lot of problems to appear and remain unsolved. And when we scale up our organisations, these misinterpretations make the problems on the whole to increase exponentially.

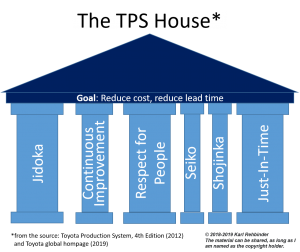

Compared to product development, production is a simple repetitive context without scaling needs for the actual work and this goes for all of the main concepts of Toyota thinking we already have discussed:

- the actual planned work – Just-In-Time

- finding the problems within the products and processes – Jidoka

- respect for people

- improving the products and processes – Continuous Improvement*

- be flexible when the context changes, leading to work force change- Shojinka

- always look at inventive ideas regarding improvements and problems – Seiko

Here is the total as a The TPS House again:

Shojinka (flexible work force) and Seiko, or to go forward (creative thinking or inventive ideas) are two concepts we need to elaborate some more on and they are not only a thinking within the teams, but of course also for the whole organisation. We can also here see that regarding flexibility, neither Agile has taken these into account with static teams (that has other benefits), nor (especially) bigger frameworks with static team of teams, roles and responsibilities. The same goes for the use of inventive ideas or trying to solve problems, where the context with a complex whole in product development makes sub-optimisation when teams solve problems. With Continuous Improvement as the only way forward regarding internal or external issues for the teams, it inevitable means sub-optimisation in Agile at scale. For prescriptive frameworks as mentioned earlier, the risk is even higher that problems brought up on the complex whole, are not accepted since the rules need to be followed at a transformation. And when our people’s voices are not heard and we not try to fix the problems within our organisation, the morale will decrease. We have without thinking about it, because the implementation plan of the new method or framework was prioritised too much, unintentionally disrespected our most valuable asset, our people. This means also that respect to our people easily can be lost at scale.

If we have unsolved problems in our organisation, it also means that our system is not stable, and can therefore not be standardized. This in turn means that we cannot do Continuous Improvement either, we need to solve our problems first. And with a lot of problems, it will be impossible to follow the Just-In-Time pillar either, since it will not matter how much we plan if we have unsolved problems. As we can see, we need to solve our organisational problems first, otherwise the whole “house” will collapse, leading to the same for our organisation.

And as we can see, it is especially at scale that all concepts are tightly connected to each other in building up the whole. Scaling can be read about in this series about common sense also in the light of the three common different types of scaling, that starts with the scaling difficulty, the number one problem for new methods and frameworks, especially those ones built on Agile. Brought up in that series is also about forces treacherously trying to make us change our common sense so we agree and adapt to a method or framework, that is apparently not sufficient regarding scaling, or have other problems. This is the same as not listening to our people, when they can see problems, that they have flagged for, remain unsolved and instead be swept under the rug. Denial of the obvious lead us to frustration, where some of the nowadays thinking is that empowerment will solve that. But, as John Seddon has stated: “Empowerment is a ‘command-and-control’ phrase (‘*I* empower *you*’)”, which also is done on the symptom or effect, meaning that it once again leads us to that the only way forward is to dissolve the problems within our organizations.

In the two earlier blog posts in this series, we can perceive the same pattern, scaling up with more teams with the same objective to achieve a bigger “project”, is not easy and often leads to a walk in the dark. The reason many times is that first the Toyota thinking has been corrupted and then converted into methods and tools without thinking about how to scale it. And with common sense again, we understand that we are only lucky if it works, since we do not understand why it works. So, a small change in our context, can rapidly lead us to a walk in the dark, since we do not understand our own new method or framework we have transformed to. But, since we humans are very adaptable, we will all try to fix our work even if the system is bad, which easily can lead to us getting burned-out. This can easily happen if we do not listen and coach/mentor/educate so the problems remain unsolved, which is disrespect.

From the series about common sense, we now understand that TPS thinking is very close to our common sense, apart from that our common sense also includes scaling thinking. TPS on the other hand, operates in a context that does never depend on scaling, even when more processes on the production line are added. The reason is that production is a context where scaling to a bigger size is not a difficult matter, since if more processes are added, they are still only connected with dependencies to only the predecessor and the successor processes. A production system is a context that is highly constrained, as Dave Snowden at Cognitive Edge would have put it. In TPS, the interface between two processes at the split line is standardized and stable and within the respective process there is standardised work description and stability as well. Every process consists of a team, that is the leaf of a big line hierarchy, which means that more processes mean a bigger pyramid, but still, that does not mean any interdependencies or dependencies for the actual work at the split line.

If we look at the Just-In-Time concept of TPS, this is regarding meticulously planning of the actual work. Also, here we can see that Agile planning within the sprint, even with their Business Value concept on the stories, as a kind of Critical Path**, has high risk to give low Flow Efficiency values, further explored here. This means that Agile is not following the Just-In-Time concept, not for a small number of teams, not even one team. And when we scale up, the Flow Efficiency gets much worse, if the interdependencies and dependencies between the teams and also between the teams and experts are not rigorously planned.

There are also other “houses” adding pillars like Flow and Innovation, which are not principles, rather symptoms of something else. Bad flow depends on queues of activities along the value flow, bottle necks, meaning that the planning (JIT) and/or that the people are not T-shaped enough, since we have only these two parameters involved in the equation. Trying to optimize on flow directly is impossible, that is only a symptom and means sub-optimisation.

Innovation is Another symptom, and here the pillar Respect for People plays an important role, since experimentation is the key to innovations. But experimentation means that you do not know the solution, which leads to continuous tries until you have gained enough knowledge for success, or if it is not possible. In an organisation where failures lead to punishment, the innovations will decrease rapidly. An introduction of detailed processes to follow in especially a product development organisation, with punishment when the processes are not followed, have the same bad effect on innovations.

The final conclusion we can draw in this series, is that Agile and all methodologies, strategies and frameworks built on Agile has only implemented some tools from Lean manufacturing, not the thinking. Agile has frankly missed most of the concepts, pillars, thinking, values and principles form TPS, due to that the many different Lean thinking alternative have become multi-intermediates, that unintentionally or treacherously is morphing the original TPS thinking. With only a few Agile teams, the teams can most probably still work things out and have great efficiency and output of the right products to their customers. But for a big organisation using a prescriptive framework built only on some Lean manufacturing tools used for a totally different context and that are not scaling, won’t help much making the organisation truly efficient in the short-term or the long-term run.

If we look at the Manifesto for Agile development, that Agile of course also is built on, we can see that the manifesto thinking is not talking about scaling (and should not). This is also pointing on that scaling up (or any other direction) is not easy, since there is no help there either.

As we can see, the toughest part in any organisation is apparently to do the scaling according to the different contexts in an organisation, where the scaling can be vertical, horizontal and when the parts of the organisation is already big or becomes bigger. The TPS thinking is not a description of how to scale, rather it is what we need to think about. We can make this short expression for the pillars of the TPS thinking which is independent of any context:

We always plan our work meticulously, and we continually are inventive and improve our products and way of working, not only by challenging, kaizen and genchi genbutsu, but also by directly taking care of and solve the problems we encounter, which we can do, by always listening to our main asset, our team-working people, and all this together become our thinking and is the reason for our successful result; we are getting healthy people that are delivering our high-quality and low cost products, with the right functionality, in time to our customers.

All of Toyota’s thinking and their principles, is pure common sense, and an elaboration on common sense can be seen in this series of blog posts about transforming our organisation with common sense.

One of Toyota’s common-senses is that they clearly differ between problem-solving (Jidoka) and continual improvements (Kaizen). By making hypothesis how the process can become a little better, PDCA cycles are done to improve the process (Kaizen), where the process is already a standalone, independent (except the material for making the refinements of the part from the former process), stable and standardized process. If we think about the takt time in many Toyota plants, 2-4 minutes and the Andon system, we can understand that the process is really stable and well-functioning as well as the output from the process, since there is no room for any real problems to solve in that short time. If the process continuously needs to pull the Andon string, there is a real problem, that need to be analysed and taken care of at the side of the production line. In this blog post we deepen when we can do hypothesis-driven work or not, which is an important matter, since it nowadays is neither analysis behind the hypothesis, nor a deep study of the result.

That was all for this series of blog post. Hope to c u soon again.

Next “chapter” according to the reading proposal tree is one of the following:

- the branch of finding the organisational principles, which starts with the series about the history of the way of working in our organisations. This branch should be prioritised first in order to understand the co-evolution between the way of working of the organisations and the market.

- the branch of problem-solving and the understanding of symptoms and root causes, which starts with the series about organisational problem-solving. This branch can be chosen when you want to learn about organisational problem-solving, since if your organisation did not follow the organisational principles from start, you will for sure need this ability. And there are always problems to solve, most often caused by ourselves, trust me on that (self-experienced) one :-). For more about built-in and normal problems, see this blog post.

Both branches will end up in the blog post series Our first trembling steps to our Methods, since both branches respectively shows a way to reach the understanding of that we need to follow science in order to succeed.

C u soon again.

*Remember that on the whole only continually improvements can be done, due to the synchronisation needed between the parts when the respective part’s improvements are executed at the same time, for example takt time change. The parts can (and must) themselves be continuously improved, as long as they do not affect another part, where the latter is highly treacherous, especially in product development.

**which has been generated transdisciplinary and iteratively with the project team and its sub-teams, common experts, stakeholders, centralised resources etc., i.e., taking also resource constraints for the total organisation into account.

References:

[1] Monden, Yasuhiro. 2012. Toyota Production System: an integrated approach to just-in-time Fourth Edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, US

Page 8, misspell; it is shojinka, and not stotinka.

[2] Toyota global home page. Link copied 2019-07-12.

https://global.toyota/en/company/vision-and-philosophy/production-system/