Of course, the team has been stressed of the bad result, and while always having the customer looking over their shoulders, reporting everything to their higher managers. But, after some weeks at the customer, the team is now home again for one month until going back again.

In a more comfortable and relaxing environment home at the office, the team starts to do some more deep analysis of the log files. They start to realise that this software, especially not the regulator algorithm, won’t do the job, since it is impossible to have different parameter setup on different train sets. Not to mention every time something is changed on the train, brakes, wheel dimension, etc., that will need a recalibration of the parameters. And then all other smaller things that do not work; over speed, late braking before a station, hard stops, jerk when passing the balise due to an updated position, etc.

And not to forget, the train simulator, where reaction time on the brakes need to be added, balises at slightly wrong positions in the track data file, odometer inaccuracy, etc., all changes needed to be able to simulate a real subway train and the surrounding rails’ hardware. The test system must behave like a train, otherwise the ATO can never be tested good enough.

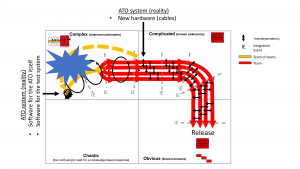

Our team is now in the Complex domain, the known Unknowns, looking for an emergent, and most probably also novel one and only solution adaptive enough to do the job for at least all train set on one subway line, but hopefully for both lines, both for the ATO and the test system. In the Cynefin™ framework it then looks like this.

The team has already started with small iterations on site, with testing day time, and analysing and changing parameters in the evening, a necessity to get fast feedback.

After one month of analysing, programming and testing in the office, the team has a new software that they bring to the customer. Fortunately, the buildings of the stations are still late, but track and trains are finished, so a lot of test time is possible. And that comes handy. For sure.

The team sees in the log files some parts they need to take care of in the software, but many things they do not know, they are still in the known unknowns, even if they have some more information. But, no one else in the total subway system is open with their information, so all information needs to be dig out, and many times the team need to prove that it someone else’s problem and that the ATO cannot solve all other parts problems. So, many bigger iterations need to be done in order to find the solution.

And as you understand, the first specification the team put in the bin. And they do not write any new specification either, because when we are in the known unknowns, what can we even write. No, the specification is instead updated continuously as the team learns about the train and feel comfortable with their solution.

After four travels, 4 weeks each with 8 hours testing required by the customer every day except Sundays, and 6 hours of analysis and small changes in the hotel room in the evenings (sometime nights), and with 4 weeks between with bigger changes, the ATO goes live at the grand opening of the subway line with the team in the train together with the customer. The team is nervous, but the head manager of the subway authority is more nervous, he has really put his whole career on the ATO installation, exchanging one of the drivers. The ATO starts from the station and drives fast and smooth to the next station and stops -20 centimetres, well within the limits of +-35cm.

In next blog post, we go a little deeper in all the changes needed.

References:

[1] Snowden, David J and Boone, Mary E. “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making”, November 2007 issue of HBR. Link copied 2019-01-19.

https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making